Going for Refuge: The Buddhist Context

The practice of going for refuge is common to all schools and vehicles of Buddhism. Historically, in the India where the Buddha first taught, people used the expression of going for refuge to declare allegiance to a chief, a powerful individual or a deity. By declaring allegiance and asking for refuge, one was promised protection from danger.

As Shakyamuni Buddha began to teach, his followers also used the language of “going for refuge” to proclaim their decision to rely on what is known as the Three Jewels (or Triple Gem) the Buddha, Dharma (teachings and pathway), and Sangha (community of followers and companions on the path).

According to early stories of the Buddha’s life, the first individuals to declare themselves followers of the Buddha were two merchant laymen. These two received the first Dharma words spoken by the Buddha, and were immediately inspired to follow his teachings. This was the only recorded case of people going for two-fold refuge as the community of the sangha had not yet been established.

In the Buddhist context, the practitioner does not expect the Buddha personally to act as a savior or to provide protection. Going for refuge in the Buddha means having confidence in the fact of his enlightenment. Going for refuge in the Dharma means believing that one can also develop qualities and awaken by recognizing the truths which the Buddha realized. This refuge in the Dharma also means adopting this pathway as an ethical pathway for daily life.

Going for refuge is a decisive formal commitment that is generally made in front of a teacher within the tradition. It is said that refuge is what defines a Buddhist. Those who go for refuge and follow the Buddhist pathway are known in Tibetan as “nang pas” or “insiders”. This refers to those who look inwards or inside—to the mind rather than following after external pleasures or goals.

We can speak of two or three levels of refuge depending upon the different vehicles of Buddhism. First is the outer or external refuge, the historical person and the teachings and community which serves as a model, instructions and helpful companions. The inner refuge is more expansive and includes all sentient beings. On the innermost level, true refuge comes in the realization of mind nature.

Audio

In this audio clip, Phakchok Rinpoche reminds us that we need to know who we are using as a model. Who or what is the true refuge object?

True Refuge: Buddha

If we consider carefully, we can understand that the Buddha is the true refuge. Let’s examine the following quote from the Mahāyānottaratantra Śāstra, (theg pa chen po rgyud bla ma’i bstan bcos), Treatise on the Sublime Continuum. This is one of the five treatises of Maitreya, transmitted to Acharya Asanga.

In Rinpoche’s teaching he indirectly refers to this well-known quote from Chapter 1, verse 21,

Ultimately, only the buddha constitutes a refuge for beings

because that great victor is the embodiment of dharma

which is the ultimate attainment of the sangha.

By this, we can understand that the Buddha comprises all three refuges. Thus, to take refuge ultimately, we take refuge in the Buddha.

Rinpoche explains that as we begin our practice of the path, we first learn what Buddha means. He notes that this can be understood on many different levels, but here Rinpoche focuses on the Buddha’s presence and activities.

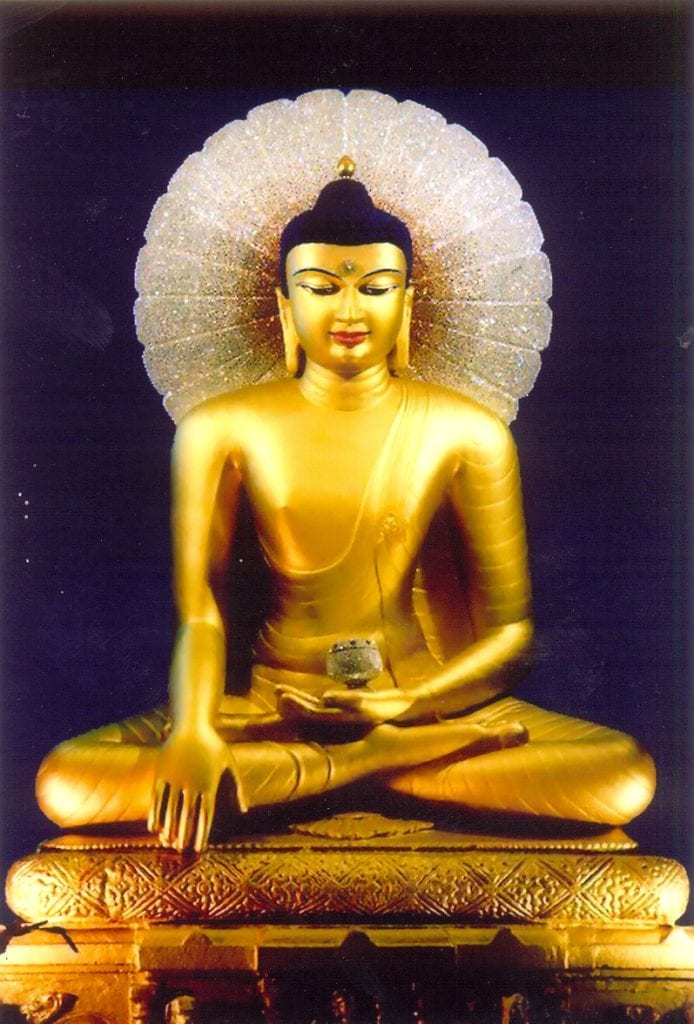

First, Rinpoche reminds us to consider the form of the Buddha by looking at an image. We practice by simply gazing at the image, letting our eyes absorb all the features.

Images of the Buddha are carefully drawn or sculpted to emphasize certain physical characteristics. There are many details we could review, and you may study the 32 major and 80 minor marks of a Buddha that correspond to specific qualities.

The 32 major marks are found throughout Buddhist literature and are described in the Pāli canon in the Lakkhaṇa Sutta. The 80 secondary characteristics are also found throughout the tradition, and they are said to be more elaborate descriptions of the Buddha’s body.

Major Marks of a Buddha

- Level feet

- Thousand-spoked wheel sign on feet

- Long, slender fingers

- Pliant hands and feet

- Toes and fingers finely webbed

- Full-sized heels

- Arched insteps

- Thighs like a royal stag

- Hands reaching below the knees

- Well-retracted male organ

- Height and stretch of arms equal

- Every hair-root dark colored

- Body hair graceful and curly

- Golden-hued body

- Ten-foot aura around him

- Soft, smooth skin

- Soles, palms, shoulders, and crown of head well-rounded

- Area below armpits well-filled

- Lion-shaped body

- Body erect and upright

- Full, round shoulders

- Forty teeth

- Teeth white, even, and close

- Four canine teeth pure white

- Jaw like a lion

- Saliva that improves the taste of all food

- Tongue long and broad

- Voice deep and resonant

- Eyes dark brown or deep blue

- Eyelashes like a royal bull

- White ūrṇā curl that emits light between eyebrows

- Fleshy protuberance on the crown of the head (uṣṇīṣa)

(List from Epstein, Ronald. Buddhist Text Translation Society’s Buddhism A to Z. 2003. p. 200)

Recalling Qualities: Meditation Technique

Rinpoche mentions several of the qualities here: the soft eyes, the joyful quality of the smile, the dignity in the position of the shoulders. Each one of these features can remind us of a particular quality. Soft eyes may remind us of love, compassion, and caring. The ”jaw like a lion” might sound strange at first, but it may help you to recall firmness and resolution. We can choose one feature as a focus and study and gradually contemplate the meaning. By slowly considering these details we can begin to appreciate the characteristics representing fruition as a Buddha.

It may be helpful to remember that reflection on the qualities and the form of the Buddha has been a traditional meditation technique and can be of great benefit. Buddhist masters often suggest that we focus on particular features as we gradually familiarize ourselves with the Buddha’s form.

Rinpoche speaks also about the qualities of the Buddha’s speech and his impartial love for all beings. And he makes an important point about the compassion the Buddha shows to followers. Rinpoche especially emphasizes the fact that the Buddha does not punish us for our wrongdoings or mistakes. Instead, like a kind parent, the Buddha supports the practitioner who needs help.