Ullambana (yu lan pen) festival is celebrated throughout Asia particularly in Chinese-origin communities, on the 15th day of the 7th month of the lunar calendar. The 7th lunar month is considered an important month to focus on merit accumulation, with immense opportunities to practice the perfection of dana (generosity). This generosity is particularly important for those ancestors who may have fallen into lower realms of existence.

Traditional beliefs common to Buddhism, Taoism, and Chinese folk religion were that during the 7th lunar month, the separation between realms opens up. During this time spirits visit the human realms looking for food and pleasure. These spirits or ghosts are believed to be people without descendants or whose descendants did not pay respect to them after death. For this reason, they are said to be troubled by hunger, thirst, and resentment. During the Ullambana festival, family members offer food and drink to these spirits and burn paper money and other forms of joss paper. The belief is that these “simulations” are valuable in other realms as currency. People also offer such replicas to wandering spirits to avoid any misfortune or intrusion upon happy homes. A large food offering may be presented for the spirits on the 15th of the lunar month. People bring food and place them on an altar or outside a temple or house, to please the ghosts and ward off bad luck.

Ullambana Origins

Merit from virtuous deeds, particularly offerings to the supreme field of merit, the ordained sangha, is transferred to deceased parents or ancestors. The origins of the festival are found in the Ullambana Sutra, the Chinese Yu lan pen jing, or the Sūtra of Boiled Rice (Taishō 685), and the Bao’en feng pen jing, Sūtra on Offering Bowls to Repay Kindness ( Taishō 686). These two sūtras describe the efforts of the Buddha’s great disciple Maudgalyāyana, to save his mother who had been reborn in one of the hell realms.

According to the Yu lan pen jing, Mulian used his psychic powers to learn that his mother had been reborn as a starving spirit (preta) and tried to offer her food.

She was unable to eat, so the Buddha advised him to make an offering to the monastic sangha in a bowl called a yulanpen at the end of the monsoon season summer retreat. The sutra advises specifically that the offerings be given on the 15th day of the seventh lunar month. Offerings made in this way are said to benefit one’s parents–not just the current life’s parents, but those in the last seven lives. In addition, it states that “six kinds of relatives,” can avoid rebirth in the three lower realms and attain heavenly spheres.

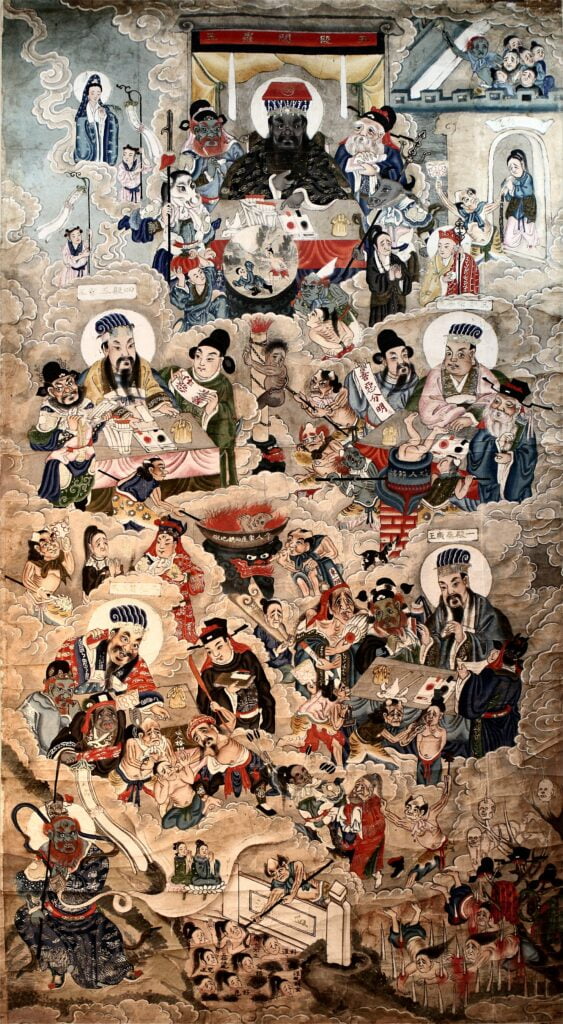

Over time, in China, the Maudgalyāyana/Mulian story became popular and led to a large number of texts. The most influential one was the 9th-century Muqianlian minjian jiu mu bianwen, The Transformation Text of Mahāmaudgalyāyana Rescuing His Mother from the Underworld; (c. 800). This text gave rise to many others as well as to illustrated scrolls, operas, and traveling productions that popularized the ritual of meritorious offerings.

Ullambana Stories Spreading through East Asia

From China, the story passed first to Korea, where it was found as early as the 6th century. And by the early 7th century it began to appear in Japan, although the earliest mentions in Japanese language date to the 8th century. But from that century on, Japanese Buddhist paintings depicted the lower realms visited by Mulian. Folk tales in Vietnam probably emerged at the same time, and there are records of the Yulanpen festival being celebrated during the 13th-15th centuries.

In Tibet, the translation of the Yulan-pen jing was translated into Tibetan by the Dunhuang master ‘Gos Chos Grub sometime in the early 9th century. And by the 15th century, expanded versions of the Me’u ’gal gyi bu ma dmyal khams nas drangs pa’i mdo (Sūtra of Maudgalyāyana’s Salvation of His Mother from Hell were being spread throughout the Tibetan sphere of influence.1Rostislav Berezki, “Maudgalyāyana (Mulian)” in Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Volume II: Lives, ed. Jonathan Silk, Brill: Leiden/Boston, 2019, pp. 591-600.

Ullambana Indian Sources

Many modern scholars believe that these two sūtras were originally composed in China to satisfy cultural emphasis on filial piety. However, more nuanced studies have demonstrated that Indian sources contain mentions of the transference of merit to parents and ancestors. In the Bhaiṣajyavastu, “The Chapter on Medicines,” the sixth chapter of the Vinayavastu, “The Chapters on Monastic Discipline,” of the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya, a tale of Maudgalyāyana demonstrates the importance of repaying the kindness of one’s parents.

The venerable Mahāmaudgalyāyana thought, “The Blessed One once said, ‘Monks, fathers, and mothers do what is quite difficult to do because they nourish their children, raise them, bring them up, feed them, and teach them everything on the continent of Jambu. Even if a son should try to carry his parents, his mother on one shoulder and his father on the other, for a hundred years; if he should give them the earth’s jewels, pearls, lapis lazuli, glass, coral, silver, gold, agate, amber, ruby, and shells; or if he should put his parents in a position of power, the son cannot truly help or sufficiently repay his father and mother with such efforts. If a person motivates his parents to have complete faith, and leads them to, leads them to enter into, and leads them to stand safely in their faith when they do not have faith; if he motivates them to have completely good conduct when they have disordered conduct; if he motivates them to be completely generous when they are ungenerous; if he motivates them to have complete intelligence, and leads them to, leads them to enter into, and leads them to stand safely in their intelligence when they have disordered intelligence, he comes to truly help and repay his father and mother with just such efforts.’ Since I have not yet repaid my mother, now I will consider where my mother has been reborn.”

Vinayavastuni Bhaiṣajyavastu, 2.326.

Maudgalyāyana used his psychic powers to see that this mother had been reborn in a hell realm. Anxious to repay his mother’s kindness, he implored the Buddha to travel to hell to instruct his mother.

The venerable Mahāmaudgalyāyana said to the Blessed One, “Honored One, the Blessed One once said, ‘Monks, fathers, and mothers do what is quite difficult to do.’ My mother has been reborn in the Marīcika world and she is one who should be trained by the Blessed One. May the Blessed One have compassion and train her.”

Vinayavastuni Bhaiṣajyavastu, 2.327.

The Buddha agreed and traveled with Maudgalyāyana to visit his mother and instruct her. After offering a meal to the Buddha and listening to teachings, she was brought onto the Buddhist path and gained the level of a stream-enterer. This narrative exemplifies the principle that the best form of generosity is the gift of the Dharma.

In China Maudgalyāyana is known under the names of (Mohe) Mujianlian, Muqianlian, and perhaps most famously in the abbreviation “Mulian”.

Ullambana Reflections in the Pali Canon

The Pali canon also preserves stories about the benefits of transferring merit to deceased ancestors. In the Petavatthu of the Pali tradition, 51 stories are told in verse about starving spirits trapped in miserable existences due to their unwholesome activities. In the Petvatthu, Maudgalyāyana (Pali Moggallāna) also plays a prominent part in learning the stories behind the suffering of beings reborn as starving spirits. In this collection of tales, the disciple who aids his mother in the realm of starving spirits (pretas) is the other great disciple of the Buddha, Shariputra. In the Sariputta story of the Petavatthu, the venerable elder meets with his mother from 5 previous lives who was reborn as a starving spirit for her stinginess toward spiritual seekers. Seeing her state aroused great compassion, and he quickly devised a plan to erect huts offering all requisites to renunciants and to dedicate the merit to his former mother. As a result of this act of generosity, she was immediately reborn as a human, able to receive and practice the Dharma.

The message of the Petavatthu can be summed up In the Tirokudda Kanda: Hungry Shades Outside the Walls. This verse provides a poetic description of the dedication of merit to assuage the sufferings of ancestors:

Outside the walls they stand,

& at crossroads.

At door posts they stand,

returning to their old homes.

But when a meal with plentiful food & drink is served,

no one remembers them:

Such is the kamma of living beings.Thus those who feel sympathy for their dead relatives

give timely donations of proper food & drink

— exquisite, clean —

[thinking:] “May this be for our relatives.

May our relatives be happy!”And those who have gathered there,

Tirokudda Kanda: Hungry Shades Outside the Walls (Pv 1.5), translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Access to Insight (BCBS Edition), 4 August 2010.

the assembled shades of the relatives,

with appreciation give their blessing

for the plentiful food & drink:

“May our relatives live long

because of whom we have gained [this gift].

We have been honored,

and the donors are not without reward!”