The Tibetan word lo means the thinking mind. The word jong translates to train, work with, purify, or refine. Thus this term in Tibetan is usually translated as ‘mind training’. Lojong teachings are also known formally as The Instructions for Training the Mind in the Mahayana Tradition.

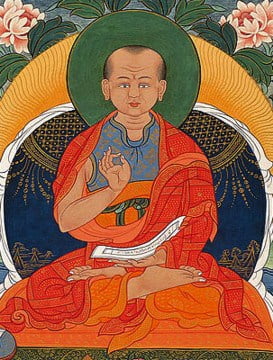

These teachings were introduced to Tibet by lord Atisha in the eleventh century. Atisha received three lines of Lojong transmission, but the best known was from Dharmakīrtiśrī on the island of Sumatra. Another prominent Lojong teacher was the Indian master Maitriyogi. Atisha secretly transmitted those instructions to his heart disciple, Dromtönpa, who then passed them on to Potowa Rinchen Sal (1027-1105). Potowa then transmitted the lineage to Geshe Sharawa Yönten Drak (1070–1141).

Lojong Training

The core element of lojong is the cultivation of bodhicitta, the mind dedicated to attaining enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings. Lojong teachings emphasize the equality of self and others. Masters stress that every living being is exactly the same in wishing to have happiness and avoid pain or suffering. The students contemplate their own experiences and then acknowledge that every other living being has the same wish.

Over time, one moves on to the difficult practice of ‘exchanging oneself for others’. Because of the courage required to fully practice these teachings, they are intended primarily for disciples of the highest capacity and were not taught widely until the time of Chekawa Yeshe Dorje (Geshe Chekawa). In this process, the practitioner works to loosen and gradually eradicate the strong sense of self-cherishing.

Key Figures in the Transmission of Lojong

The most prominent teachers were known as the Kadampa masters. The tradition became known as Kadampa in reference to those who teach the Buddhist scriptures (bka) by means of personal instructions (gdams). These include Atisha’s chief disciple, Dromtönpa Gyelwé Jungné, Geshe Langri Tangpa, Geshe Potowa, and Geshe Chekawa. In addition, Shantideva‘s classic work, the Bodhicaryāvatāra, contains clear practical advice for cultivating the meditations that cut through the habitual ego-centered outlook.

By thinking of all sentient beings

As more precious than a wish-fulfilling jewel

For accomplishing the highest aim,

I will always hold them dear.Whenever I’m in the company of others,

I will regard myself as the lowest among all,

And from the depths of my heart

Cherish others as supreme.In my every action, I will watch my mind,

And the moment destructive emotions arise,

I will confront them strongly and avert them,

Since they will hurt both me and others.Whenever I see ill-natured people,

Or those overwhelmed by heavy misdeeds or suffering,

I will cherish them as something rare,

As though I’d found a priceless treasure.Whenever someone out of envy

Does me wrong by attacking or belittling me,

I will take defeat upon myself,

And give the victory to others.Even when someone I have helped,

Or in whom I have placed great hopes

Mistreats me very unjustly,

I will view that person as a true spiritual teacher.In brief, directly or indirectly,

I will offer help and happiness to all my mothers,

And secretly take upon myself

All their hurt and suffering.I will learn to keep all these practices

Eight Verses of Training the Mind by Geshe Langri Tangpa

Untainted by thoughts of the eight worldly concerns.

May I recognize all things as like illusions,

And, without attachment, gain freedom from bondage.