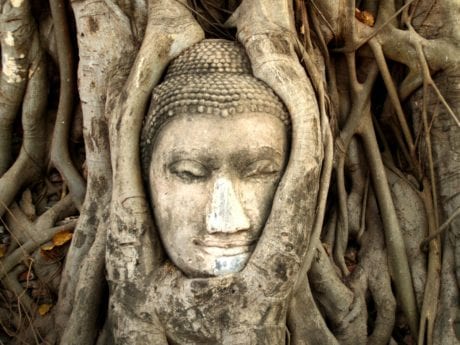

Over 2,500 years ago, a man sat under a Bodhi tree and had a completely radical insight: suffering was caused by ignorance about who we really are. This ignorance comes from a habit. To quote Kyabje Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, that habit is “the constant evaluation of experience.” That simple habit is responsible for all our discontentment, and it prevents us from insight into the fundamental nature of ourselves and all phenomena. Everybody still has a mind, just like they did 2,500 years ago. And this mind, that we are all blessed with, can be an enormous source of joy or sorrow. Yet so much of the time we act as if our happiness depends on having the right stuff or creating the best circumstances, and that usually leads to disappointment. It’s the same problem now as it was 2,500 years ago. But, since it’s a habit, we can do something about it.

What is Radical?

Radical means root, and also has a sense of doing something that is counterintuitive. To be well within ourselves, we need to find the root of wellbeing and get to know it. That root is the basis of the mind. It’s the mind that is happy or sad, jealous or joyful, angry or loving.

In our Dzogchen tradition, teachers will often use a special metaphor to explain our predicament. It’s called the difference between a lion and a dog. When you throw stones at a dog, it chases the stone. This is how we are with our thoughts and emotions. We chase every thought and emotion and play with, think about it, get into it. On the other hand, if you throw stones at a lion, he doesn’t care about the stones at all, he turns to look at where the stones come from.

We spend our whole life preoccupied with our stones—our thoughts and emotions. We never even look at the source of the thoughts and emotions, the mind itself, the awareness that knows the thoughts and emotions. So learning how to first stop habitually chasing our stones, and then to learn to look at the stone thrower, awareness, that is just as radical an activity today as it was 2,500 years ago.

How to Stop Chasing Stones

The first step is to get used to refraining. Refrain from what? Refraining from habitually chasing our stones—the thoughts, emotions and sensations that arise in our mind. We do this by giving our mind a job. It can be as simple as placing our attention on our breath, or placing our attention on the needs of others. We get used to placing our attention on something, and then being mindful that our attention stays where we put it.

In the beginning, it seems almost impossible, our mind seems to jump all over the place, and we keep forgetting to bring it back. Gradually, by doing this again and again, every day, we get used to it, and it gets easier and easier. In this aspect, it doesn’t matter if you do sitting meditation, tonglen, ngondro, or sadhana practice, the principal is the same: remain stable, in the face of whatever thoughts, emotions or sensations arise in your mind.

Looking at the Stone Thrower

Having gained a degree of stability, our mind is more calm, more flexible. Then we can begin to investigate, who is having the thought. Who knows the thought? Like a lion turning to look at the stone thrower, we turn to look at our stone thrower, the essence of mind itself.

Let’s say if you are the stone thrower and the lion turns to look at you, what happens next? There are exactly two possibilities:

- You run away

- You get eaten

In other words, you (the stone thrower) disappear and there are no more stones. Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche said all the time, “Don’t look at the thoughts, look at what thinks!”

This is the beginning of understanding Buddha’s radical insight into the nature of everything. This is the beginning of learning to be happy without relying on circumstances. This is the key to being happy—satisfied and content—with everything just as it is.

Responses