It is the first evening of the Mahamudra retreat (July 2019) at bucolic Rangjung Yeshe Gomde, and a dozen or so sangha members have gathered in the meditation hall, aka: the barn. We are waiting to receive instruction from Tulku Migmar Tsering, teaching at the invitation of Kyabgön Phakchok Rinpoche in his absence. As I begin to settle on the meditation cushion, it dawns on me I’m on a bit of a retreat streak. It’s only been about a week since I completed a 5-day Dzogchen retreat downstate, which culminated in taking refuge with Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche. This occasion took place after dipping in and out of Buddhism for twenty years or so. The whole experience has barely sunk in, but I can feel myself hoping the momentum won’t ebb. Despite my fears about falling out of touch with the dharma again, for the time being, I am steeped in it, and even though this is my first visit, I am struck by familiar kindness at Gomde. It might sound a bit cliché, but I am very much at home; still, I can’t help but wonder if I’m ready for Mahamudra instruction.

As we wait for Tulku Migmar, I take note of my physical surroundings. The big barn itself is shamelessly purposeful. One might even mistake it for being a converted stable—and one would be correct. The humble facade and vaulted roof contain a vast, open floor plan with a couple dozen “private” lodgings, each with doorless door frames and windowless window frames. These lovingly constructed rooms built from handsome boards of unadorned solid pine encircle the meditation hall itself, whose walls reach only a fraction of the way to the geometric rafters above. The building literally offers openness and spaciousness, despite the stillness of the air on this particularly muggy summer night.

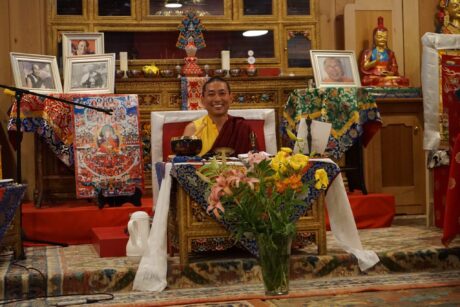

Someone strikes a gong near the barn’s entrance; most of us stand at attention. A moment later, an excited yet constrained voice brings the rest of us to our feet. “Tulku-la is coming.” He enters the hall and breezes by the sangha, each person in a posture of deference to greet and honor our teacher; his legendary smile precedes him. He prostrates and takes his seat; we prostrate and take our seats. Beholding Tulku Migmar Tsering sitting on the throne with a retinue of masters gazing over his shoulders, I can’t help but think of my introduction to Tulku-la earlier in the day. Is this the same man who was casually hanging out with the sangha in the dining room a few hours ago? The same easy-going, affable, almost ordinary gentleman who happily conversed with us over snacks? Where was his entourage? Where was the air of unapproachability I had come to associate with great teachers? I began to wonder if our modest teacher was a consolation prize.

Tulku Migmar is all business as soon as we begin the prayers before the teaching session, but what immediately follows utterly transforms my notion of what makes for a masterful teacher. The instruction begins and Tulku-la gets to the point, “Meditation without preparation and learning is not correct.“ There’s no humor or slack here. He goes on, more softly now. “(For) all sentient beings… the nature of mind is the Buddha.” I hear him. I believe everyone does. His smile spontaneously returns and washes over the sangha. Two minutes into the teaching I’ve decided, plain and simple, Tulku Migmar Tsering is the real deal. There’s nothing superfluous about this man. I cannot detect a shred of pretentiousness or guile. His accessible presence hasn’t changed one bit now that he has assumed the full authority of his role. His disarming, flashing smile says, “this happiness belongs to you, too.” It is the happiness of realization, and it is contagious. I think to myself that the sangha is in very good hands and I begin to relax in a way I’m not accustomed to.

This embodiment of wisdom and kindness feels miraculously ordinary. Tulku-la teaches, we make offerings, we pray, we are offered the dharma. We make thanks again. Our teacher rises, and we rise. Tulku-la passes by us on his way out of the meditation hall, a hall of smiles. The evening’s discourse is over before I can fully digest what I’ve heard, but that’s not out of the ordinary.

What is out of the ordinary is that I feel for the first time in my life that the profoundness of the dharma isn’t something out there, on a pedestal, hidden behind layers of pageantry, dogma, or personality. It is here, made transparent by a man who stands eye-to-eye with everyone he meets.

The following morning I am awoken by the gong that would keep the sangha informed as to the start of a meditation session, or the arrival of Tulku-la, depending on how emphatically it was struck. I slowly but happily transfer myself from my sleeping quarters to my self-designated cushion in the meditation hall. I’ve never been a morning person, but I’m grateful to sit with Tulku-la and the sangha and refocus before my monkey mind wakes up.

Immediately after the morning meditation one of the sangha members offers guided qi gong instruction right outside the barn. It’s a beautiful practice, and a perfect way to keep the body’s energies moving. My own meditation background includes adhering to a tradition that frowns upon excessive movement or exercise, at least while in retreat. But there is no such restriction here at Gomde, and thank goodness—the land practically begs to be explored. A few trees scatter their shadows across the rolling grass of the center; thick forest lines the edges. Before breakfast I wander the quiet, unmarked surrounding roads on foot. The walk is dappled with glassy ponds and picturesque clearings. The sky feels closer here than most places. The pace and space around Rangjung Yeshe Gomde perfectly compliments the vibe of the center itself. There is no sense of urgency or haste. It’s not just relatively quiet here, it is truly serene. The noise of my mind actually seems louder than usual against this peaceful backdrop, but I’m not bothered—it makes sense.

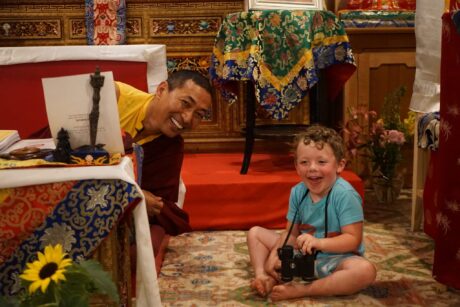

A clanging cowbell lets everyone know it’s time for breakfast at the the small barn. No one touches the plates or silverware or sneaks a nibble. We’re waiting for Tulku-la, and he’s mercifully punctual. He’s all smiles, which would prove to be his default countenance for the entirety of the retreat. He serves himself and sits at the head of the family-style table arrangement. We follow suit and enjoy the first of many meals as a sangha. Tulku-la joins us not in retrospective silence or withdrawn piousness, but as a familiar friend. Well-intentioned and occasionally giddy banter swirls around the small barn; when conversation steers into deeper waters, Tulku-la is ready to share, whether by listening with a nonjudgmental ear, or speaking with a nonjudgmental heart. It would be like this nearly every breakfast, lunch, and dinner except when he could not be there with us. There is a palpable sense of camaraderie and friendship, even on this first day. After the meal each of us washes our plates in the kitchen while dedicated volunteers get to work on their yogi jobs around the center.

Later in the morning another crash of the gong sounded—it was time for sang. The sangha positioned chairs and cushions around the sangpo beneath a brilliant blue sky. Not even 10am, the sun was making its strength known. I had never made smoke offerings before, but I felt welcome to sit in for the experience—one of a number of “firsts” throughout the week. My eagerness to participate would eventually lead to a deeper understanding of the practice and its accompanying texts, but not without immense support from the more experienced members of the sangha. I was graciously offered guidance and instruction whenever I had a question, and sometimes even when I didn’t! There was always someone nearby to notice a quizzical or flummoxed expression on my face. Thanks to that almost clairvoyant awareness and attention, by the end of the week I was navigating the practice texts with enough confidence to occasionally offer help to another newcomer. It was a relief to be invited to step into these offerings, to generate and dedicate the merit, and to have an opportunity to develop a deeper relationship with the teachings themselves. The effortless generosity generated by the sangha and Tulku-la helped me realize I had the right and the ability to learn these practices, if I would only be willing to receive them. Maybe it was me; maybe it was the sangha; maybe it was Tulku-la, but this act of asking and receiving felt like a revelation after years of scattered efforts trying to do it all on my own.

I could recall and share dozens of memorable moments during the retreat—such as the sublime pond-side meditation, the hysterics that ensued when Tulku-la used a bit of foul language during a teaching, a gloriously lucid question and answer session beneath the trees, or beholding a field of fireflies beneath a sequined night sky. But what I want to share most of all was the way Tulku Migmar offered us Mahamudra. With the aide and artistry of Oriane Lavole, our incandescent translator and friend, Tulku-la painted pictures of the dharma using timeless anecdotes, personal stories, and straight teachings from the Masters before him. Phakchok Rinpoche too was ever-present both in spirit, and in the form of audio and video clips which at times left the sangha basking in the spaciousness and clarity of the dharma. Not content to simply march through a schedule of rigorous instruction, Tulku-la sensed the sangha’s need to explore both the teachings and our own lives as a means of transmitting wisdom. This willingness and ability to connect our own personal experiences to Mahamudra was done so effortlessly, it hardly seemed to be happening at all. The week was a living conversation that fulfilled my need for retreat, discipline, reflection, practice, and most unexpectedly, connection. It was the kinship shared between Tulku-la and the sangha that brought the dharma down to Earth for me, and for that gift, I can only bow.

And smile.

Responses